PUBLISHED IN DOSSIER

Talkin’ New York

David Yurman recalls formative places in the city that shaped him.

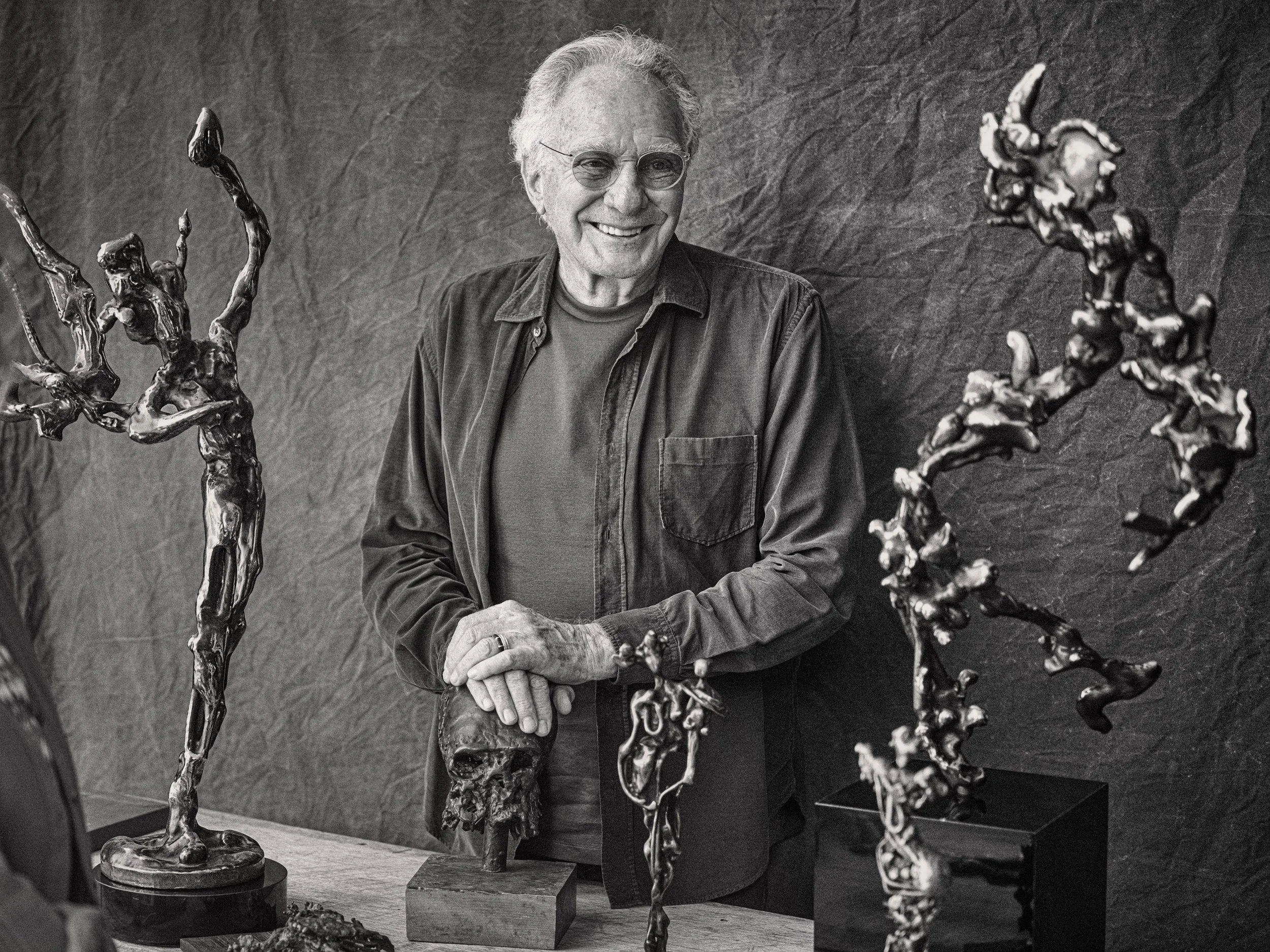

DAVID YURMAN IS A BORN-AND-BRED NEW YORKER, an identity ever present in his eponymous brand — one of the most recognizable in jewelry today — with 60 stores around the world. But like his hometown and the jewels crowning his creations, David Yurman (the man) is multifaceted. Despite his brand’s stratospheric, star-studded rise, he’s maintained an artist’s spirit, a cheeky irreverence, and an air of mysticism. Above all, he possesses something one might presume dissipates with such global success: soul.

The man loves horses: “They’re very empathetic. I don’t ride. I just go out and hang with them.” He is fascinated by quantum physics: “We’re not lost individuals — we’re connected to everything.” He stresses the importance of the journey: “We’re all spiritual beings so busy wanting to know the answer before we’ve gone through the process of asking all the questions, and that’s where the information is — in the process, in the doing.” Showing him my own David Yurman pieces — a sparkling necklace and cocktail ring I wear both to weddings and to the grocery store — he smiles wistfully, remarking on the two buyer archetypes: Buy and Show and Own and Own. The first? One who purchases to telegraph something to the outside world: status, belonging, etc. “They don’t keep it to their heart as much; they completed an outfit.” But the second? That’s the buyer whose pieces become a part of them. “You’re wearing David Yurman jewelry not to impress. They’re close to your heart. So you connect to it. You are my ideal customer.”

A David Yurman piece is unmistakable. Like its creator, who has had many incarnations — he’s been a dishwasher, a sandal maker, a hitchhiker, and more — it possesses grit, glam, and a hardy urban nature that could only come from New York City. Here, he shares some of the places across the city that have shaped his vision.

One City, Many Lives …

I was born in New York, lived in the Bronx, moved to Long Island for high school, then moved right back to the city. I apprenticed as a sandal maker and hung out at the coffee houses back in the beatnik days. I was washing dishes in Gerde’s Folk City because I could listen to music. I heard Bob Dylan’s first songs. I couldn’t stand his gravelly voice. I thought: He can’t hold a harmonica? He’s got this prosthetic thing around him. I love him now, but his first sound was a bit like Dave Van Ronk. [Dylan] was such a snooty little kid. But he was an incredible poet — a poet of the times. He deserves what he’s become. … Anyways, I went to New York University. I apprenticed for the sculptor Hans Van de Bovenkamp on the west side. I went to art school in New York. I hitchhiked to California, and even when I was in California — which I loved, so open and free — New York was like, “Okay, let’s get back to work. You’re not gonna live on abalone and ferns.” I apprenticed with Theodore Roszak, who was [an elected member of the Fine Arts Commission] in New York and a brilliant sculptor. My friend Bob Berg had Farm and Garden Nursery, so I sold Christmas trees there, and then in the spring and summer, we planted gardens in penthouses. I decorated the New York Stock Exchange for Christmas two years in a row. Going in at, like, 7 o’clock at night, you finished at, like, 3 in the morning. Putting garlands over everything. This is it, the bastion of capitalism! We’re making it green.

I’ve lived in [Greenwich] Village. I’ve lived uptown, at The Apthorp, which is this great old building on 79th Street. I had a little penthouse. This is my home. I’m just now realizing it, believe it or not. I’m 82 years old, and only in the last few years have I thought, Yeah, I’m a New Yorker.

New York’s Greatest Qualities …

Diversity. We’re all living here together, so many different people — we coexist. The focus is on entrepreneurship — on making good food, good clothing. It’s creative, industrious. It’s a good place to learn, because the marketplace is here. It’s an economic center. It is one of the great cultural cities. The great museums, great plays. It’s a place for all the arts. And the arts are essential for human existence. No art? No culture, no people, no happiness.

The Meals That Made Me …

The two go-tos — I hate to mention this because your readers are going to be disappointed, but not as much as I am — En [Japanese] Brasserie [closed in 2024] and the other one that’s gone is Giorgione on Spring Street. That was my kitchen. I would go there sometimes three times a week. Cavatelli with broccoli rabe and sausage — I probably had that every time. The owner was Giorgio DeLuca, of Dean & DeLuca. He knew produce. How they made food was an art and a craft. The same as Jean-Georges restaurants; if there’s a Jean-Georges anywhere in the world, I eat there. You feel welcomed, and that’s important. The Odeon, it’s just a go-to. It’s still crazy busy. The salmon’s always great. The hamburger’s spot on. Steak’s great. The fries are unbelievable. Notice everything’s walking distance from our loft!

Thirty years we’ve been eating at Omen [Azen]. I do all the pickles and shiso. Rice. The soup is unbelievable. They have a sliced steak. The black cod is as good as, or better than, the one at Nobu. I very seldom drink beer, but I always drink beer [at Omen]. You need that bitter, sharp, bubbly break between the intensity of the taste. It just cleans the palate. I used to go to Fanelli’s years ago. Now I eat at Walker’s when I have a friend in from out of town. It’s fancy.

I like to get most of my pastas at Raffetto’s on Houston [Street]. I also like eating at Cipriani. They do a noodle with a casserole with cheese and ham that is — can I say to die for? To live for? And they would allow me to take my dog in a little bag, so he was okay to go inside. It’s not really a pickup joint, but it’s wealthy, spoiled trustfund babies there. I took my granddaughter there, and my son Evan said, “How did you honestly take her there?!” I didn’t realize! I took her there for the pasta!

When we go uptown, Sant Ambroeus. The one in the Village is small, intimate. The one uptown, you think you’re in Milan. They still wear the jackets. They’re very proper. And service is great. The little desserts and little sandwiches. How does tuna fish taste so good? And, hey, that’s what makes New York great. It accepts anyone who has the grit to build a business. You just have to be welcoming and all for quality. You gotta be welcoming.

A Neighborhood That Has My Heart …

We’ve lived in Tribeca for over 40 years. Tribeca Park on Greenwich Street — my son Evan took his first steps there. I remember just sitting back and watching him play. There was nothing better on a Saturday or Sunday — one when we weren’t working. When you grow up in a place, you don’t realize that it’s as important as it is in building your character and your family.

Outside our window, this triangle used to be filled up with sanitation trucks and equipment. It’s now a park. The trees are incredible, and birds are now there. That was a change that, actually, the gentleman who runs our archive, Richard Barrett, and a few other people made. There’s a law that says if a place was ever a park and was changed into something else and you want to legislate it returning from the city dump yard, you can [challenge] it. (Ours was a green space back in the 1810s). We marched with placards.

That New York spirit [of community activism] — Lou Reed. Debbie Harry. They were all part of that. The artists were a driving force. Art isn’t just something you hang on your wall. No, no, no. Art is a spirit. You get artists involved? You have a fucking pit bull on your ankle. They do not give up.

Only in New York …

Walking 23rd, 24th, 26th streets, which is a weird place to walk. Funny shops, bead shops, and Singer sewing machine repair shops, the flower district … whole different energies. Inspiration finds me in a place I feel somewhat lost but comfortable. If you have open time, drift down 10th Avenue, with all the restaurants, Hell’s Kitchen, even 59th Street all the way west. That’s really one of the oddest streets around. There’s no real order, but there are pockets of communities and businesses that serve these communities. Like the Garment District. They still have the racks rolling the clothing around. There’s something nostalgic and real about it. People are doing things. You feel that energy. This is quantum theory. Take a glass of water: If you look at it, the water’s molecular structure would appear a certain way. When you leave, the atoms are different because they’ve been observed. That’s what mystics knew years ago: Everything affects everything.

New York in Milan …

We went to Milan to visit Armani. We went to the workshop. They don’t do tours; I don’t know how we got in. And believe me, Mr. Armani knew we were there. He’s amazing. There’s a picture of him standing in front of a window. Just the way he was standing, I knew he was dressing the window. Someone would say, “What difference would it make?” It makes a lot of difference to Mr. Armani. He’s doing something that means something to him. We went to his shop and saw them working. Someone had purple hair, another had cut-up jeans, the next had gauges in their ears — all doing their thing. They were all kinds of people in the studio that were doing the handwork. It’s craft. And that feeds into everything he does. And we do the same.

Editor’s note: A few weeks after this interview, Giorgio Armani sadly passed away.

My Quiet Place …

The Cloisters. My grandson and I go there quite a bit. There’s a little building attached to it. It’s a hippie kind of lunch place, lots of granola.